Displaying items by tag: ginseng

Don’t hate the diggers. Hate the ginseng game.

A ginseng digger works a hollow somewhere in the Appalachians. Traditional ‘sangers’ generally follow centuries-old protocols for sustainable harvest of the plant and pose much less of a threat to ginseng than habitat destruction and extractive industry. Photos from American Folklife Collection/Library of Congress

A ginseng digger works a hollow somewhere in the Appalachians. Traditional ‘sangers’ generally follow centuries-old protocols for sustainable harvest of the plant and pose much less of a threat to ginseng than habitat destruction and extractive industry. Photos from American Folklife Collection/Library of Congress

Wild ginseng is declining, but small-scale ‘diggers’ aren’t the main threat to this native plant — and they can help save it

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Justine Law is an associate professor of Ecology and Environmental Studies at Sonoma State University.

KNOXVILLE — Across Appalachia, September marks the start of ginseng season, when thousands of people roam the hills searching for hard-to-reach patches of this highly prized plant.

Many people know ginseng as an ingredient in vitamin supplements or herbal tea. That ginseng is grown commercially on farms in Wisconsin and Ontario, Canada. In contrast, wild American ginseng is an understory plant that can live for decades in the forests of the Appalachians. The plant’s taproot grows throughout its life and sells for hundreds of dollars per pound, primarily to East Asian customers who consume it for health reasons.

Because it’s such a valuable medicinal plant, harvesting ginseng has helped families in mountainous regions of states such as Kentucky, West Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina and Ohio weather economic ups and downs since the late 1700s.

Ginseng collection banned in Pisgah, Nantahala national forests

The long maturation time of American ginseng makes it susceptible to overharvesting. A ban on collecting the plant in Nantahala and Pisgah national forests remains in place. Illstration: Ohio State Extension Service

The long maturation time of American ginseng makes it susceptible to overharvesting. A ban on collecting the plant in Nantahala and Pisgah national forests remains in place. Illstration: Ohio State Extension Service

Wild populations of the plant remain too low to sustainably harvest

Adam Rondeau is a public affairs specialist with the U.S. Forest Service.

ASHEVILLE — The Forest Service pause on issuing permits to harvest American ginseng in the Nantahala and Pisgah national forests will remain in place for the 2024 season.

Efforts to restore ginseng populations on both national forests continue. However, wild populations of the plant currently remain too low to sustainably harvest for the foreseeable future. The plant is known as both a folk and medical remedy and preventative for myriad ailments.

“We stopped issuing permits for ginseng harvesting in 2021, when the data began to show a trend toward lower and lower populations each year,” said Gary Kauffman, botanist for the National Forests in North Carolina. “We’re seeing that trend reversing slightly, but ginseng plants take a long time to mature before they reach the peak age to start bearing seeds.”

Native to Western North Carolina forests, wild ginseng is a perennial plant that can live for 60-80 years. It can take up to 10 years before a ginseng plant will start producing the most seeds; however, overharvesting in the past has made older plants increasing rare.

Ginseng: The root that helped shape a region

An interview about ginseng with expert and author Luke Manget

This story was originally published by Appalachian Voices.

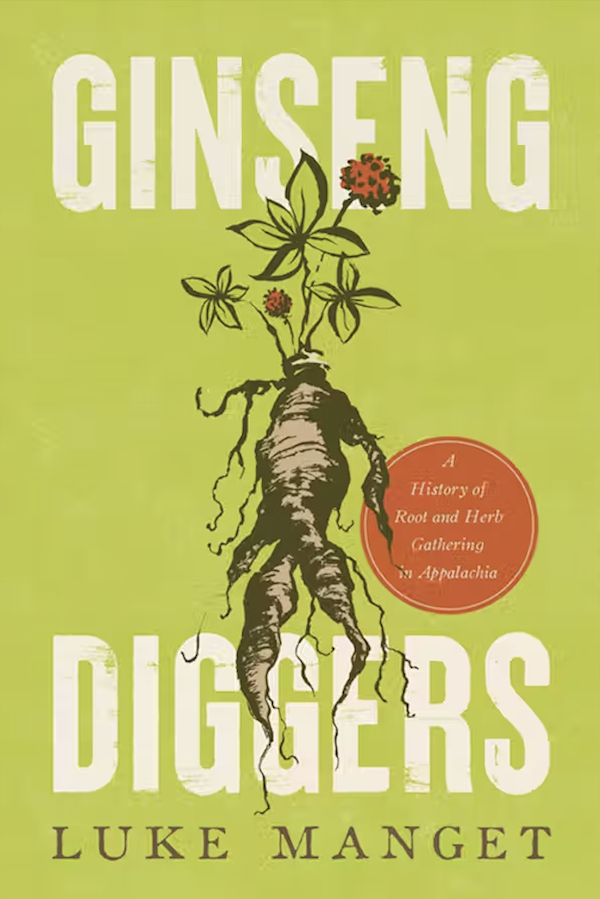

An author and historian who traveled across Appalachia examining business records of pharmaceutical companies, mountain entrepreneurs and country stores, Luke Manget’s book, Ginseng Diggers: A History of Root and Herb Gathering in Appalachia, unearths the complex and impactful history of ginseng and root digging. Manget delves into the relationship between a valuable root and a region’s cultural identity, transition to capitalism, and land use. The book was published by the University Press of Kentucky in March 2022.

The Appalachian Voice: Can you tell me a little bit about your background and what drew you to the history of ginseng?

Manget: My family on my mother’s side is from Eastern Kentucky and I grew up visiting family a lot. I grew up hearing some of these stories and my grandmother talked about digging mayapple behind the house. I was always kind of fascinated with it. When I was in graduate school for history and looking for topics to write about, I started looking into how the Appalachian region recovered from the Civil War in the late 19th century period and kept seeing references to root digging and ginseng. I immediately became fascinated by this idea and wanted to know more about it. It was a family connection, but it was also part of my desire to figure out subsistence practices in Appalachia and how they were altered and how they were changed by the Civil War.

Tragedy of the commons: Plant poaching persists in Smokies and other public lands

A red trillium is seen in the Southern Appalachians. It is often the target of poachers who aspire to place it in an ill-suited domestic ornamental garden. Courtesy Wiki Commons

A red trillium is seen in the Southern Appalachians. It is often the target of poachers who aspire to place it in an ill-suited domestic ornamental garden. Courtesy Wiki Commons

Forest service withholds ginseng permits to protect native Southern Appalachian plants as overall poaching persists

Paul Super has a message for people who take plants and animals from Great Smoky Mountains National Park:

It’s stealing.

“We’re trying to protect the park as a complete ecosystem and as a place that people can enjoy the wildlife and everything that lives here … but they have to do it in a sustainable way, and poaching doesn’t fit,” said Super, the park’s resource coordinator.

“Be a good citizen. Enjoy the park without damaging it.”

Super said the novel coronavirus pandemic led to the second-highest visitation to the park in 2020, just over 12 million, even with the park being closed briefly.

“This year will likely have the highest visitation ever,” he said, adding that the park is, in terms of the pandemic, a “relatively safe place for family and friends.”

Super said this higher visitation rate may lead to more poaching but it may also lead to more people who “appreciate something that a poacher would take away from them.

“Besides being illegal, that’s just selfish and rude,” Super said regarding plants and animals, and even cultural artifacts that are taken from the park.

Super is the park’s research coordinator, and is in charge of recruiting researchers to help better understand the nuances and full ramifications of stealing public natural resources. He said his researchers don’t enforce the laws, but they do alert law enforcement rangers to poaching incidents and suspicions.

- ginseng poaching

- poaching in great smoky mountains national park

- poaching in southern appalachia

- pink lady slipper

- ginseng

- smokies ginseng

- trillium

- great smoky mountains national park

- paul super

- smokies research coordinator paul super

- is removing plant from mountain illegal?

- insect poaching

- rare plant species

- ginseng trade

- butterfly poaching

- beetle poaching

- big south fork poaching