“We’re literally losing ground, and that’s not going to stop,” said Todd Crabtree, the Tennessee state botanist and member of the state Natural Heritage Program.

“To prioritize protection, we need to know where ecologically valuable species exist,” said Crabtree, whose conservation work has been guided at times by DeSelm’s analysis.

Were it not for the efforts of some determined individuals at the University of Tennessee and beyond, DeSelm’s collection of precious point-in-time terrestrial data might have been lost forever. Instead, researchers, botanists and conservation specialists have an immense collection of data about the state’s natural landscapes as they were, are, and could be again.

The records from the small white-oak copse atop Cherokee Bluff represent the challenges inherent in compiling the database.

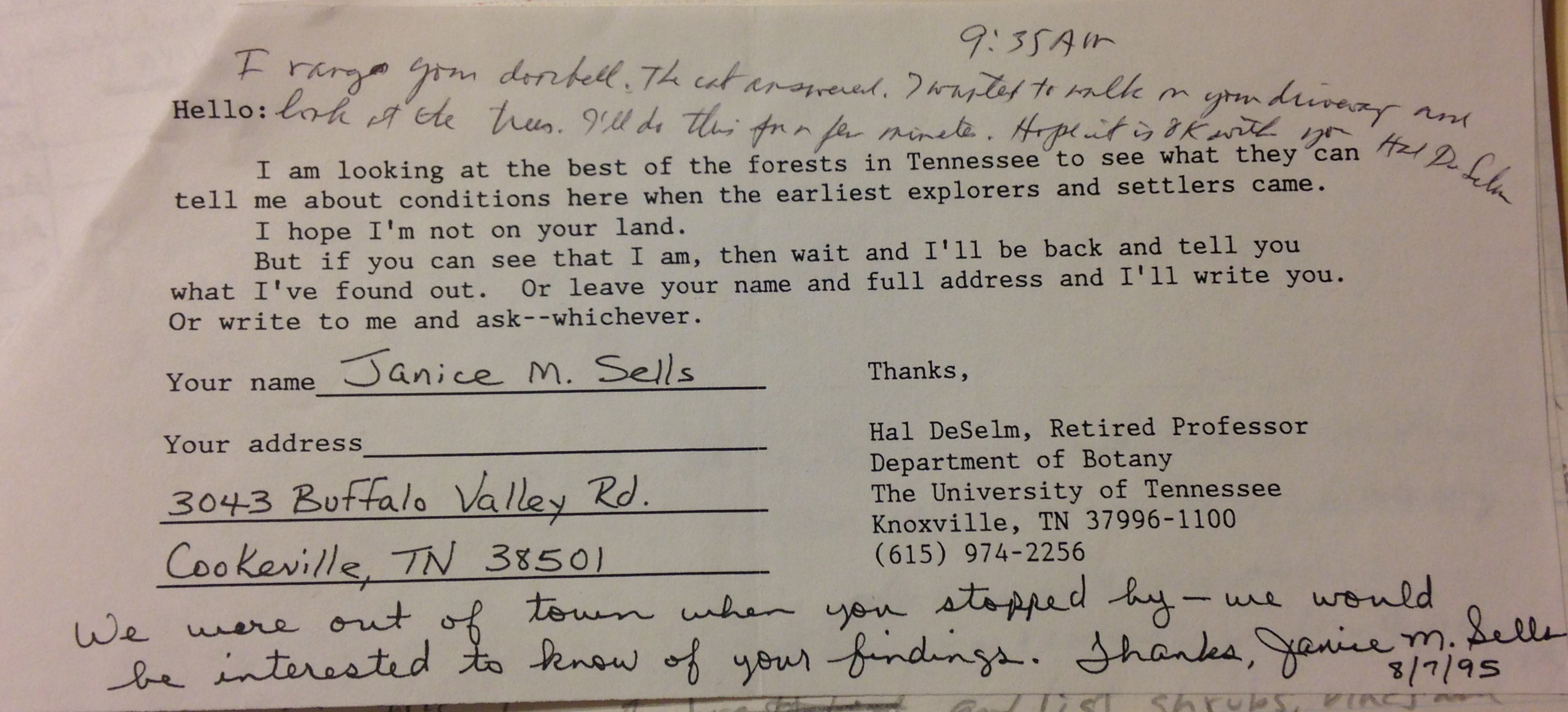

This is one of DeSelm’s quad maps, on which he scrawled plot locations. Courtesy UT Tree Improvement Program

This is one of DeSelm’s quad maps, on which he scrawled plot locations. Courtesy UT Tree Improvement Program

DeSelm, a Marine veteran, recorded his findings the old-fashioned way: on field sheets, index cards and dog-eared maps. Using multiple codes and values, he noted by hand the forest type and dominant tree and ground cover; herbaceous growth; tree size; understory; canopy; soil type and a variety of other observations. DeSelm assigned a plot number to the small patch of forest perched above the river, and determined its coordinates. He would later add geology and bedrock values.

This is the view from one of DeSelm’s vegetation plots atop Cherokee Bluff in Knoxville. Thomas Fraser/Hellbender Press

This is the view from one of DeSelm’s vegetation plots atop Cherokee Bluff in Knoxville. Thomas Fraser/Hellbender Press

“Hal was one of the last, true boots-on-the-ground naturalists,” said Belinda Ferro, an ecologist with the Clinton, Tennessee office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

She was searching for historical literature and research related to the relationships between soils and plant communities — especially barrens and glades — when she got wind of DeSelm’s collection just a few months before he died in 2011.

True to his old-school methods, Ferro wrote DeSelm a letter asking for access to his research. DeSelm, whose health was failing, responded enthusiastically, and the two met, just once, to discuss his collection.

“He knew his time was limited,” she said. “He was desperate to get that work out into the world.”

Esham went to Scott Schlarbaum, a UT professor she knew would be interested in preserving the DeSelm archives, and the two hatched a plan to form a “ragtag” DeSelm Papers committee via the UT Tree Improvement Program and secure some funding and labor to preserve and digitize the vast paper collection. The oversight board was largely made up of DeSelm’s previous graduate students — now respected professors, ecologists, foresters and researchers.

The committee received permission from DeSelm’s widow, Bea DeSelm, a longtime Knox County commissioner, to move his vast data and correspondence collection to the UT Herbarium, then housed in the Hoskins Library.

Schlarbaum and De Selm were acquaintances, but “I had no idea he had been taking all this plot data,” Schlarbaum said. He went to the herbarium to take a look at the data collection, and he was both fascinated and alarmed.

“This dataset is irreplaceable,” he said. “I knew that right away.”

Boxes were on tables. Some were in cabinets, and some were on shelves. People would come in occasionally and view some of the files, and Schlarbaum knew from experience this paper data had to be preserved in a more secure environment. “People come and pick through these things, and a lot ends up getting pitched,” he said, referencing the loss of some early Tennessee Valley Authority natural history records. Schlarbaum’s work to preserve the records wasn’t “out of sentimental reasons. I knew how valuable they were,” he said.

But before the papers were secured for posterity’s sake, they had to be assembled into a useable database that could be shared upon request with conservationists, botanists and ecologists. That task fell to project manager Allison Mains, who had earlier worked for Schlarbaum as a research assistant.

“It just so happens I’ve always wanted, oddly enough, to take somebody’s full set of data and put it in digital form,” Mains said. She was already familiar with field work through her previous masters research on threatened and endangered birds, so she was somewhat intuitively and experientially prepared to create the database.

There were challenges, though, when she began the database project in 2012. It took her four years to digitally catalog all of DeSelm’s work. She entered all plot data and codes by hand into a database; she took and stored digital photographs of his worn field sheets and topographical and county maps covered by his scrawl.

Each point had at least two 8-by-14 paper field sheets of data connected to it, including vegetation, understory, types of plants, and tree size. She entered it all by hand, and learned some of DeSelm’s quirks as evidenced in the data sheets. Sometimes he’d trip up on some math, or be slightly off with his coordinates. And his “handwriting was an art form.”

If Mains couldn’t decipher something, she’d send it to herbarium manager Gene Wofford, who worked with De Selm for years in the UT botany and ecology departments. If Wofford couldn’t read it or explain it, he’d pass it down the line to another De Selm associate.

Some of his records and maps were even bloodstained. He apparently squished a bug or two while filling out his field sheets. He would also include random notes to himself, such as “need new shoelaces.”

“I felt like I was in his world but I never met him,” Mains said. “He had an incredible amount of data he continued to collect on his own time and own dollar; he just kept plugging away.”

The database includes DeSelm’s sampling conducted primarily from 1993 to 2002, but there was likely some overlap with his earlier academic work.

Despite the relatively archaic data-collection methods, he was very systematic in the way he collected and stored information, she said. “He was very organized and very deliberate about what he wanted to do.

“Everything was neatly filed and tucked away, but there was a lot of it. He was incredibly organized, though. He saved everything,” Mains said. Not just the raw data, but correspondence and notes of conversations he had while out in the field. The files also included newspaper clippings of articles he thought were important, thank-you cards, letters and correspondence with other botanists.

Some of the correspondence included responses to notes he’d leave on property owners’ mailboxes after canvassing their land. Many were curious and appreciated his efforts; however, “He got one that threatened his life with a rifle,” Mains said.

Despite the occasional threat from a landowner, he completed his mission of sampling virtually every vegetative community in all but one Tennessee county, though he ultimately ran out of time to compile the information into a book.

But there is now a database accessible (by permission) to those interested in the original — and changing — composition of Tennessee’s terrestrial landscapes and some of the state’s most sensitive plant communities.

DeSelm visited dozens of other sites in Knox County over the course of his canvass, painstakingly recording the forest and other natural landscapes in his quest to document the true terrestrial nature of Tennessee before European settlement.

The oldest data point is from 1973, but he was most active from 1993 to 2002. He compiled a rich trove of data from every Tennessee county (except Lake), from the Great Smoky Mountains and Roan Highlands to the Cumberland Plateau and bottomlands of West Tennessee. His ultimate goal was to publish “The Natural Terrestrial Vegetation of Tennessee,” a comprehensive look at the native flora of the state.

De Selm’s records provide a natural baseline and reference point, and “you can learn what’s happened to a piece of land over time,” Ferro said. DeSelm had plots all over public lands such as Great Smoky Mountains National Park (including Cades Cove and Thunderhead Mountain) and Tennessee Valley Authority land, but he also sampled many landscapes on private land.

Plot by plot, as he worked over the course of his career and into his retirement, he was amassing a valuable trove of data for scientists like Ferro. “There are places I never would’ve found,” without DeSelm’s data, she said. “I use it all the time. I’ll use it to the end of my career and beyond.”

The information has been used by Esham to describe the relationships between some soil types and plant communities, and Tennessee Natural Heritage Program scientists have used the database to identify rare or threatened plant communities. Plants of economic and cultural value, such as ginseng and goldenseal, also appear in the database, which is among the reasons the database can only be accessed with permission.

“His data gives me hints there are some things out there we need to investigate,” said the state’s chief botanist, Todd Crabtree. DeSelm focused on evergreen barrens rich with rare and threatened species for a large part of his career, and many such sites are included in the database.

The DeSelm Papers, however, describe many ghosts of landscapes long gone. A pawpaw patch he noted above the Little River in Townsend was paved over during the widening of U.S. 321. Many sites in West Knox County are under asphalt thanks to the boom in commercial developments such as Turkey Creek. Skeletons of once-great hemlocks stud entire Appalachian slopes, victims of the exotic woolly adelgid.

DeSelm’s work, and those who labored to organize it and share it with the greater science community, also provide hope for restoring the forests, barrens, bogs and natural prairies of Tennessee to the way they really were before exotic plants and insects, mining, logging, farming, reservoirs and commercial and residential development cast many such natural areas into oblivion.

“He described a world we don’t have access to anymore,” Mains said.

In a lot of cases, however, the plots remain and retain the features DeSelm described. Like the grasses and upland plant communities of Thunderhead and Cades Cove. Like a vine-draped expanse of mixed-oak forest off Mount Olive Road in South Knoxville. Like a bog off the Alcoa-Maryville greenway. Like the mixed-oak woods atop Cherokee Bluff, which still exist, largely in the state DeSelm described — just in another point in time.